Lakes are in B.C., Manitoba, Newfoundland and Labrador, NWT and Nunavut… By Terry Milewski , CBC News

CBC News has learned that 16 Canadian lakes are slated to be officially but quietly “reclassified” as toxic dump sites for mines. The lakes include prime wilderness fishing lakes from B.C. to Newfoundland.

Environmentalists say the process amounts to a “hidden subsidy” to mining companies, allowing them to get around laws against the destruction of fish habitat.

Under the Fisheries Act, it’s illegal to put harmful substances into fish-bearing waters. But, under a little-known subsection known as Schedule Two of the mining effluent regulations, federal bureaucrats can redefine lakes as “tailings impoundment areas.”

That means mining companies don’t need to build containment ponds for toxic mine tailings.

CBC News visited two examples of Schedule Two lakes. In Newfoundland and Labrador, the Vale Inco company wants to use a prime destination for fishermen known as Sandy Pond to hold tailings from a nickel processing plant.

In northern B.C., Imperial Metals plans to enclose a remote watershed valley to hold tailings from a gold and copper mine. The valley lies in what the native Tahltan people call the “Sacred Headwaters” of three major salmon rivers. It also serves as spawning grounds for the rainbow trout of Kluela Lake, which is downstream from the dump site.

Lakes ‘safest option’: mining association Vale Inco’s proposal was the subject of a public meeting on June 10 in Long Harbour, N.L. Billed as a “public consultation” on the proposal, the meeting was attended by government officials, mining executives, environmentalists and fishermen.

Lakes are often the best way for mine tailings to be contained, said Elizabeth Gardiner, vice-president for technical affairs for the Mining Association of Canada.

“In some cases, particularly in Canada, with this kind of topography and this number of natural lakes and depressions and ponds … in the end it’s really the safest option for human health and for the environment,” she said.

But Catherine Coumans, spokeswoman for the environmental group Mining Watch, said the federal government is making it too easy. She said federal officials are increasingly using the obscure Schedule Two regulations to quietly reclassify lakes and other waters as tailings dumps.

“Something that used to be a lake — or a river, in fact, they can use rivers — by being put on this section two of this regulation is no longer a river or a lake,” she said. “It’s a tailings impoundment area. It’s a waste disposal site. It’s an industrial waste dump.”

Coumans said the procedure amounts to a subsidy to the industry and enables mines to get around the Fisheries Act.

“What Canadians need to know is that this year, from March 2008 to March of 2009, eight lakes are going to be subject to being put on Schedule Two, which is just about every mine that is going ahead this year is looking around, looking for the nearest lake to dump its waste into.”

A local environmentalist who attended the Long Harbour meeting, Chad Griffiths, said of Sandy Pond: “It’s easy enough to consider just one lake as just one lake, as a needed sacrifice, right? But it’s not one lake … It’s a trend. It’s an open season on Canadian water.”

‘Open season on Canadian water’: environmentalist

A test case: the Red Chris Mine in northwestern B.C.

Last fall, a Federal Court judge ruled that federal bureaucrats acted illegally in trying to fast-track the Red Chris copper and gold mine without a full and public environmental review.

The decision put the project on hold, but late last week, the Federal Appeals Court reversed the decision, paving the way for federal officials to declare lakes to be dumps without public consultation.

Imperial Metals said in a release Monday that federal authorities “are now authorized to issue regulatory approvals for the Red Chris project to proceed,” although the matter could still be appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada.

In the earlier decision, Justice Luc Martineau overturned the decision by federal officials to skip a public review, saying it “has all the characteristics of a capricious and arbitrary decision which was taken for an improper purpose.”

He also found those officials “committed a reviewable error by deciding to forgo the public consultation process which the project was statutorily mandated to undergo.”

The dump site includes two small lakes in a Y-shaped valley. Imperial Metals plans to build three dams to contain mine tailings within the valley. But environmentalists say there is no way to stop effluent leaking downstream in groundwater.

Jim Bourquin of the Cassiar Watch Society, a conservation group, said Kluela Lake, immediately downstream from the site, is “one of the best trout fishing lakes in northern B.C.”

“This is a precedent-setting decision by the federal government to start using fish-bearing habitat as a waste management area,” Bourquin said. “It’s totally bizarre for the federal government to come here and say that this Y-shaped valley up here is no longer a fish habitat, it’s no longer sacred headwaters, it’s just a waste dump site.”

But Steve Robertson, exploration manager for Imperial Metals, told CBC News the dump site will be sealed and that the economic benefits of the planned Red Chris mine will be enormous.

“This is a project that can bring a lot of good jobs, long-term jobs, well-paying jobs to a community that desperately needs it,” Robertson said.

He added that the total investment over the 25-year life of the mine would be about half a billion dollars and that the risk to the environment will be carefully managed.

“Tailings are part of the mining process,” Robertson said, “and, if treated properly, if they’re built into a proper structure and kept submerged, they should be able to withstand the test of time and actually not pose a detriment to the environment.”

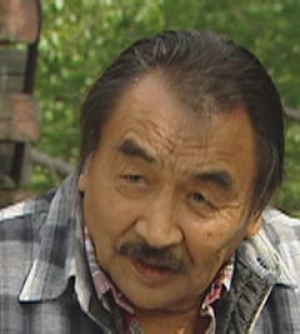

But James Dennis, a 76-year-old elder of the local Tahltan people, told CBC News he doesn’t buy that.

“We want it stopped,” said Dennis, who lives in the native village of Iskut, 18 kilometres northwest of the mine site. “We want to stop the mine … The animals will be drinking that water and they’ll all be polluted too.

“Once they do the mine, they’re going to leave, and we’re the people who are going to live with that. Not me, but my grandchildren, the small little kids like this. That’s who’s going to live with the pollution.”